THE SEMIOTICS OF PHOTOJOURNALISM

Robert Doisneau: Accuracy and Truth in Photography

The purpose of this essay is to examine how language within photojournalism operates and illustrates ideas of accuracy and truth. The vehicle through which this idea will be explored is through the work of 20th century French Photographer, Robert Doisneau. Doisneau, in his time, would have never been considered a photojournalist, yet he pioneered a groundbreaking type of photography known as “humanistic photography.” This style aims at documenting the world around us in a way that preserves the integrity and “truth” of the moment, while simultaneously illustrating the subject through a creative lens.

Accuracy and truth, as this paper will further develop, are two entirely different concepts. Accuracy describes photography’s ability to capture reality point-by-point in all exactness. Accuracy, specifically in photojournalism, is exclusively objective in nature. The aspect of truth however is, by its nature, subjective. By examining the work of Robert Doisneau, this paper will establish the distinctions between the two ideas and also create a way to interpret an image and distinguish each idea.

Ultimately, this paper arrives upon two different, yet connected, conclusions. The first remains that Doisneau’s style of photography opened the medium of photography to a new way of inspiring both a visceral and emotional reaction while remaining objective and informative. In addition, this paper concludes that photojournalism demonstrates the greatest ability to inform ideas in an unbiased way. In doing so, a photojournalistic image creates meaning that is specific to each individual, creating truth on an isolated level.

Introduction

There exists a long-held dichotomy in photography. Many argue that as this media captures reality so perfectly, it may not be categorized as art. Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, a French inventor, was credited with the first permanent photograph in 1825, and as the founder of the art and mode of communication (Newhall 13). Photography has always encountered of a level of scrutiny, especially following the period between 1958 and 1965.

During this time, many camera manufacturers flooded markets with new technology that provided mainstream individuals the opportunity to participate in an emerging art, without in depth technical knowledge or financial burden. As technology became increasingly available and user-friendly, photography became an activity as simple as point and shoot, requiring minimal expertise or creative design (Hamilton).

Many argue that the art of photojournalism was born along with the Frenchman Robert Doisneau in 1912. Doisneau became known as the “poet of Paris,” through his photography depicting the city on a day-to-day basis, proceeding, during, and following WWII. Self-taught, Doisneau’s work set the precedent for the photojournalistic style in that his images expressed ideas, events, sentiments, etc., in a way that emulated reporting(Hamilton).The time and place in which Doisneau was born encompassed a certain Zeitgeist in that the general mystique of Paris, in conjunction with the spirit of the era, seemed to naturally give way to this type of photography.

The idea of photojournalism as a form of art can be very unsettling to some artists. Photojournalism captures reality as it exists, and the amount of creative vision required, some say is minimal, if non-existent. However, in the early 1960’s, French writer François Cali commented on an emerging ideology that persists to this day, stating, “One hundred good photographs explain immediately, and infinitely better, than one hundred pages of text, certain aspects of the world, certain current problems” (Hall 143).

Many photographers of the period, including Doisneau, embraced this ideology. Thus, the idea that photography could serve as a form of language was born. This leads to the chosen research question: how does the language in a journalistic style of photography, specifically the work of French photographer Robert Doisneau, illustrate and convey ideas of accuracy and truth?

Within this discrepancy between the actual event being documented and the chosen way in which an artist illustrates the event, lies the artistic value or meaning of a journalistic style photograph. Photography is, by its nature, an objective form of media. The study of language, or Semiotics, allows for a broader understanding of this idea. The signified, or the subject itself, which is described by the signifier (words on a page, an image, etc.), is so dynamic and uniquely flexible in nature for the viewer, that it can illustrate and embody the truth specific to each and every member of an audience.

A photographer captures something tangible in an attempt to describe something indefinite, something within us that is exclusive to each individual. As photojournalism is naturally objective, the unique reaction elicited by the signified, specifically Doisneau’s work, creates meaning, or the sign, that is unique and specific to each individual, creating truth on an isolated level.

Research

Can a photograph lie? This suggests a photograph, or any kind of visual media, has the potential to think and act according to its own desires or whims. The photograph itself naturally cannot pose a lie, but the fashion in which the idea or event is expressed retains the potential to deceive. Gustav Le Bon, a French Philosopher reasoned in his 1895 piece, Psychology of the Masses, that the masses can only conceptualize ideas as image; thus, the potential for an image, in its ability to control by deception, is unmatched by any other form of media (Noth). This philosophy maintains heightened importance for Doisneau, as the 20th-century was an era driven by war, resultant propaganda, and the power of an image.

Paintings, drawings, etc, maintain a greater proclivity than a photograph to convey a sense of language in a twisted or deceiving manner, whereas a photograph serves as an “indexical sign.” Many in the field of photographic semiotics support the theory that photography acts as an indexical medium. Noted German linguist Winfried Noth explains that a photograph corresponds point by point to nature, recording an event, person, landscape, etc., in a calculated, (referencing to the idea of accuracy) exact fashion (Noth). In a matter of words, photography is the epitome of accuracy.

He concludes that photography, above any other medium of visual expression, is semantic in nature in that it deals with anything that emanates from nature in a precise fashion. It may be reasonable to conclude that Robert Doisneau’s photojournalistic style captured Paris throughout the 20th -century in all exactness and in a non-polemic or “apolitical” fashion. Thus, Doisneau’s style supports the ideas expressed by Noth’s extended description of truth in photography.

La Violin d’Ingres Man Ray, 1924

Deception in photography typically stems from any attempt to alter an image, and in the digital age, misleading images have become commonplace in the world of politics, law, history and science. Prior to the digital age during Doisneau’s time, double exposure (the repeated exposure of photo paper under the influence of multiple negatives to create a new sign or value), solarization, and other darkroom retouching methods served as the basis of photographic “deception”.

Even still, Doisneau’s journalistic style, as opposed to the Emmanuel Radnitzksy’s (Man Ray) surreal style of photography, emulates Noth’s description of photographic realism and truth. Surrealist images, particularly those of Man Ray, did not seek to deceive for malicious purposes. Rather, these images, like the one shown here, attempted to create an elevated sign by rendering the subject through a uniquely different lens.

Famed 20th-century photographer, Richard Avedon, maintained an idea regarding accuracy and truth in photography that aligns with Noth’s previous description, as well as possibly challenging it. Mr. Avedon holds that, “the moment an emotion or fact is transformed into a photograph it is no longer a fact but an opinion. There is no such thing as inaccuracy in a photograph. All photographs are accurate. None of them is the truth”(Avedon).The idea that photography captures nature point by point in an indexical fashion corresponds with Avedon’s idea of accuracy in a photograph. Avedon seems to suggest that truth exists on a universal level, an understanding that can be applied to all individuals in all situations.

This disagrees with Noth’s idea that truth is a result of photography’s indexical nature. As a result of its ability to precisely capture a subject in a way that mimics reality, the potential a photograph has to convey truth is inherent and undeniable. Avedon would suggest in response that the photograph, without interaction from the photographer or the camera is truth, but only without the presence of that interaction.

For example, as photojournalism is naturally objective, or indexical, the moment an event is captured, it is no longer something natural, but now subjective. In the act of capturing an event and expressing it in a way that is unique to the photographer, i.e. the art, the expression becomes subjective. Avedon’s quote relative to the lack of truth an image maintains, supports the idea that photography establishes ideas of value, rather than truth, in an isolated fashion. Stated differently, in photography, fact becomes opinion, or the objective becomes subjective.

In semiotics, there exists an important difference between denotative and connotative language, which ultimately influences the sign; this difference in photography provides the potential for the medium to convey a sense of language (Port). Denotative meaning derives from the specific description or word ascribed to the referent, while connotative meaning describes the emotional reaction held in responses to a series of qualitative modifiers.

For example, the word, “barn” elicits an image of a red building that houses animals along with other agriculturally centered objects. If one were to say, “look at the rustically beautiful example of early 20thcentury architecture,” and in response, another replied, ”what, that giant, rusty, dilapidated rats nest, you mean?”, the two are discussing the same structure, but the connotative meaning is drastically different.

Noted pictorial semiotician Göran Sonesson discusses in his thesis Semiotics of Photography – On Tracing the Index, the idea of the denotative power in a photograph, or in similar words, the vocabulary of photography. In his paper, Sonesson expands on the idea, held by Spanish born photographer Joan Costa, and pictorial semiotician Hartmut Espe, that a photograph maintains two separate informative planes: a content plane and an expression plane, or, a denotative plane and a connotative plane.

Without the presence or context of the content plane, the expression plane or the “free space for creativity” is meaningless. Sonesson describes the interaction of the two planes as “resemanticization.” Costa created a system that measures the potency and influence each field has on the pictorial sign by placing a square grid over an image, which would ultimately serve as the way in which the two planes are measured. On the following page, Costa’s grid has been placed over one of Doisneau’s arguably most iconic photographs, taken after World War II in 1950.

Le Baiser De L’Hotel De Ville Doisneau, 1950

Le Baiser de l’Hotel de Ville serves as Doisneau’s cornerstone of humanistic photography. Following the war, many photographers, European and American, began to stray away from the techniques used in the 30’s. These techniques utilized an “overt formalism and composition” (Hamilton, 138), such as a skewed horizontal, which served to convey a sense of motion in order to elicit feelings of presence with the subject in the audience. In his time, Doisneau never would have been considered a photojournalist, as the term and idea did not exist.

However, this movement away from aesthetic technique, with a newly emphasized focus on capturing an event in a realistic and accurate sense, rather than elevating it unnecessarily in a contrived manner, marked the beginning of a movement in photography that would eventually give birth to the photojournalist. Subjektive Fotograpfie as it was known in Germany, Neo-Realismo in Italy, and in the United States, Social Documentary Photography or “Concerned Photography,” Humanistic Photography prevailed as the primary visual means of chronicling events, or in Doisneau’s case, culture and daily activity (Hamilton).

The following image is of the same photograph on the previous page, but with Costa’s denotative or “content” plane filled in with white squares. The denotative plane of this image occupies 45.6% of the total image, while 54.4% of the image exists in the connotative plane, or the area of free creativity. Without the denotative plane, it is impossible to determine what this image depicts, its purpose, or to achieve any kind of visual coherence. However, once the white squares are removed, it is clear the image depicts a couple kissing amidst a busy Paris street.

The denotative plane of the photograph acts as the direct language of the image, conveying objectively and in an unbiased fashion, the content and purpose of the image. The connotative plan in any photograph serves as the harmony to the melody that is the subject. It gives the denotative plane purpose in the sense that without it, a formulated photograph with a complete meaning to an observer is impossible. People develop truth based off of experiences and the understandings developed from those experiences. Stated simply, experience is the context for an individual’s truth, as the connotative plane is the context for the subject, or denotative plane.

Only 7% of human communication is verbal while the remaining 93% lies within body language, tonality, as well as other inherent yet subtle actions. That 93% acts as the coloring, the context described earlier. The context, or expression plane, serves as the foundation of the “art” of an image, specifically a journalistic shot. A subject is placed within an expression, or context, in order to elevate and conceptualize the language.

The expression plane is subject to, due to its inherently ambiguous nature, various rationalizations, hence, connotative. In an Avedonian sense, it is fair to conclude that the denotative plane is the basis of any truth in a photograph, in that truth is created on an individual level. This truth is then further heightened and contextualized by the expression plane. The reason a photograph, captured with the influence of the “humanistic style,” can exist as a piece of art, as well as an expression of truth, lies within the distinction and relationship between the connotative and denotative planes.

As established by Mr. Avedon, once the photographer captures the event, or “intervenes,” the event captured in the image no longer exists as fact, but now as opinion. The relationship between the two communication planes in an image serves as the basis for a journalistic photograph’s potential to remain artistic while conveying an idea of “truth.” As a photograph is “omnitemporal and omnispatial,” as Mr. Sonesson states, it requires an individual to infer the information void from the photograph.

Unlike the indexical point to point representation that a physical indentation unto the earth, such as a crater, marking that a meteor struck here, a photograph seldom remains in the location in which it was taken (“Camera Lucida”). This being case, the pictorial sign, or value created from the interaction of the two visual planes, expression and content, is similar to that of a verbal sign in that it remains unaffected by the physical world.

Here exists the key difference between active art and passive art. Active art describes the process of taking an intangible feeling, idea, or pictorial sign, and expressing it through the vehicle of an artist (drawing, painting, sculpture, etc.). Photography may be considered passive art as the sign is created as a product of the image. When active art is subjected to time or space, it becomes diluted or even irrelevant in that an artist removed from the audience by time and space created the sign.

It can be debated that a painting is not necessarily incapable of conveying “truth,” but that it merely seems that it remains incredibly limited to a wide range of people across space and time. The ability of a photograph to retain meaning one hundred years after an event has taken place, after the subjects of the image have grown old even possibly passed, the buildings torn down, and the trees removed, speaks to the pictorial sign of the photograph and its ability to remain adaptive and potent.

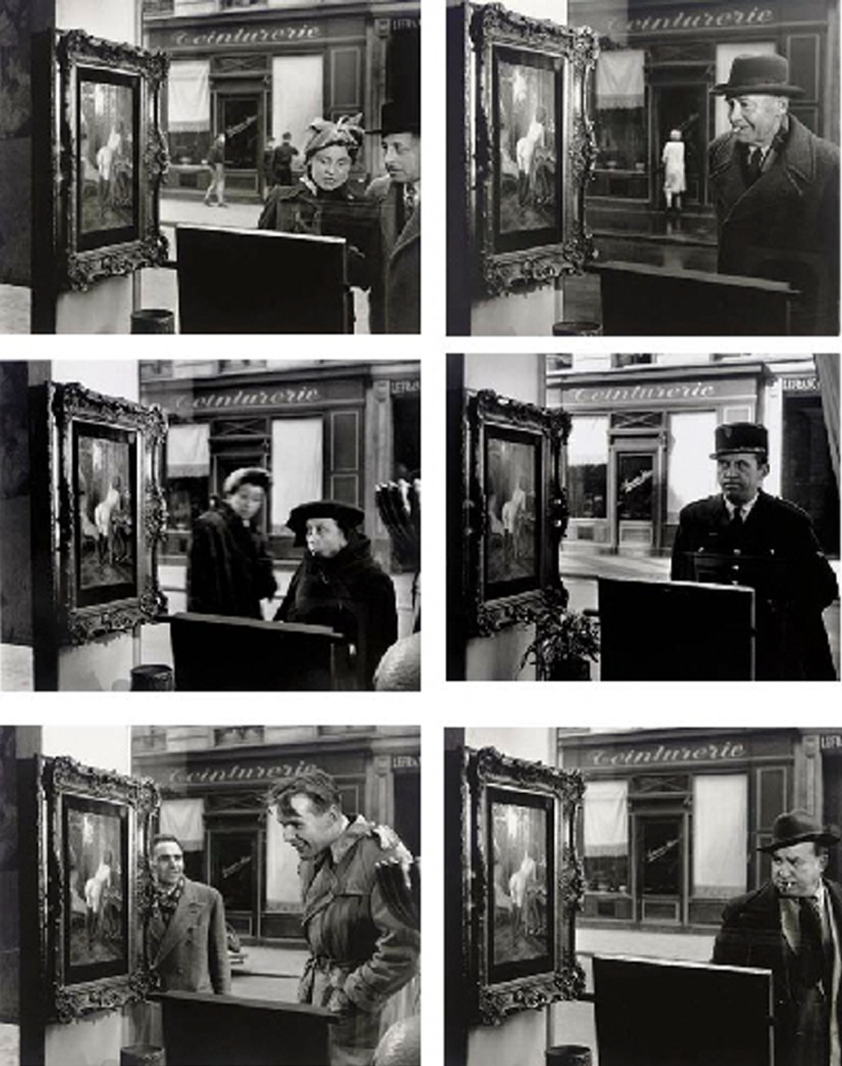

Le Regard Oblique Doisneau, 1949

This collection of images, taken by Doisneau in 1949, was a continuation of his popular “photo-novels,” a series of images describing day-to-day life of a group of individuals. Many of these novelettes were published in leading magazines such as LIFE and the French publication Point de vue. Doisneau’s associate and antique vendor friend, Robert Miguel, purchased a racy Wagner painting of a nude woman, which he placed in his street window.

The two noticed the attention the image was getting soon after it was placed in public view. Doisneau decided, as there was a reflection in the glass and no one could see him taking photographs, to chronicle the viewers and their subsequent reactions. All of the photographs were captured within a 2-3 hour period. This series again demonstrates Doisneau’s affinity with the narrative image, or as it is known now, photojournalism. Doisneau described this collection as comique terrestre or “down to earth comedy” (Hamilton).

This series offers a concise and specific narrative concerning the people of France in the late 40’s; in addition, it seems that this series remains true to the humanistic and journalistic tendencies Doisneau championed, an organic style, as the image was not placed in the window so that he could capture the reaction.

Let us apply Costa’s grid to the following image, one example in Doisneau’s series Le Regard Oblique or, “The Sideways Glance.” In this image, the content plane or denotative plane has become much more specific and focused, compared to Doisneau’s Le Baiser de l’Hotel de Ville. The referent offering narrative has become extremely narrow, yet it remains equally as informative. The content plane is marked with white squares.

Only 5.6% of this image remains in the denotative plane, or the specific aspect of the image that is offering the narrative, while the remaining 94.4% of this image only serves to contextualize and elevate the referent, or language, of the image. Exactly 40% less denotation exists here than in the Le Baiser piece, even though it remains equally, if not more apt, at conveying a narrative. This series demonstrates the photographic sign’s similarity to verbal sign in that it is equally dynamic in its ways of communicating meaning, narrative and truth.

It seems however, that these images, like the rest of Doisneau’s work, maintain a sense of observation, rather than intervention. It would seem that this idea provides a photojournalist with the ability to capture in both the denotative plan and connotative plan. The inherent comedy of the image, or resulting sign, seems to transcend time and space as Sonesson would suggest, which again supports the adaptability of pictorial sign in photojournalism and the similarity it maintains with verbal sign.

As discussed previously, many pictorial semioticians regard photography as an indexical medium in that the signifier correlates directly, whether physically or visually, to the signified. In language, words are ascribed as signifiers to everything people can conceptualize, interact with on a sensory level or understand in an arbitrary manner. “Universe” for example, is completely arbitrary in nature in that a certain collection of sounds are aligned to describe something intangible, in a sense, and impossible to fully see, and therefore conceptualize. Symbols (words) typically must be taught, whereas an index, such as a couple kissing intimating a close relationship (the relationship of A to B) is the result of any sensory interaction. An icon describes the signifier that in a literal way resembles the signified.

Onomatopoeias exist as a common form of iconic semiotics, such as the word “hiccup” directly mimics the sound created by the action (Port). Again, sensory interaction is key in defining iconic sign. Many theorists, such as Phillip Dubois, argue against the notion that photography is indexical. Dubois supports that photography is iconic in nature in that it is a mirror of reality, or as inventor and photography pioneer Fox Talbot described the medium, “the pencil of nature” (Port). Many even argue that a photograph can be a sign as it depicts reality in a coded way. While all of these theorists agree that photography maintains the potential to express ideas of “truth,” the fashion in which it achieves this is specific to its semiotic classification: symbol, icon or index.

Doisneau’s humanistic style of photography embodies, unintentionally it may seem, flavors of iconic, indexical and symbolic sign. It is clear that the purpose of a photojournalistic, humanistic, etc., photograph remains to establish that the captured event, has happened illustrated in a visual way. This is the definition of an indexical sign. At the same time, Doisneau’s work acts as a mirror and preserved record of a time past, an enumeration on the definition of iconic sign.

As the 19th century progressed, demand for Doisneau’s work before and during WWII rose significantly as those now in their latter years were looking for a nostalgic account of their youth (Hamilton). Photography’s potential as symbolic sign can be dangerous as symbolism can act, especially in imagery, as the basis of deception. However, the symbolic sign of a photograph, in conjunction with the previously mentioned content planes (denotative and connotative) remains the place where the emotional reaction stems.

Richard Avedon’s ideas suggest and support the notion that truth, as a result of a photograph, can only be established on an individual level due to its subjective nature. That “visceral truth” stems from photography’s symbolic nature. Similarly to the idea that the connotative plane serves to elevate, contextualize and conceptualize the denotative plane, a photograph’s iconic and indexical potential make possible the elicitation of an emotional and personal truth. The index itself maintains little to no purpose or relevance without the presence of the symbolic potential.

In the early days of film, it was dismissed as an effective form of art, media or medium for the communication of ideas, as it captured the world around in an indexical fashion. The question was raised, “why go into a dark, cramped room to see what could be seen outside in the light?” This idea references an indexical photograph without any kind of symbolic sign.

L’Amour Sous L’occupation Doisenau, 1940-1944

During the Nazi occupation of France from 1940 to 1944, Doisneau captured a striking series of images depicting the life of the French in the newly formed State of France, no longer the Republic of France. The image entitled, L’Amour sous l’occupation, or, “Love during the occupation,” depicts a young couple sitting against the backdrop of both the Tuilerie Garden in Paris and barbed wire (Hamilton).

It can be concluded that the image itself is iconic in nature, yet it remains composed of a number of varying indexical signs. The first clear Indexical sign is that of the couple embracing. While this index conveys a truth that can vary slightly from individual to individual, it revolves around notions of commitment, love and connection.

The embrace remains indexical as those ideas may be inferred and observed as a product of the visual representation. A different indexical sign is that of the barbed wire, indicating some kind of military or authoritative presence. Once the two indices are juxtaposed against each other, a new sign develops around ideas bolstered by the symbolic words used to title the piece. Impressions of forbidden love surface along with an increasingly focused perception of a possible purpose of the denotative plane: rebellion.

To elaborate on a previous idea, the unique truth exists as the product of the interaction of the two visual planes, in conjunction with necessary connection and presence of all three forms of sign: symbolic, iconic and indexical. The emotionally potent, accurate and trenchantly informative medium of photojournalism has existed and will remain an important vehicle to communicate sign for a mind that, as Le Bon articulated, may only conceptualize and think in image.

Conclusion

From its conception in the mid 19th century, photography ignited a revolutionary movement of communication in an artistic and uniquely informative way. The potential of an image to speak, convey ideas of sign or meaning, had existed since Paleolithic images of cattle appeared on cave walls. However, with the inception of photography, a unique mixture of iconic, symbolic and indexical sign had the potential to meet in a provocative way. This created a new visual medium that allowed an individual to capture an event in a journalistic and indexical fashion, while still portraying it in an artistically captivating way that could elicit the emotional tendencies of any individual.

An image’s dynamic mix of denotative and connotative content allows that image to objectively convey purpose while at the same time allowing the audience to fill in the void and establish their own meaning or “truth.” Photography is unique in that it retains the ability to communicate on an omnitemporal and omnispatial level, creating a unique sign to an individual, regardless of space and time.

Doisneau’s humanistic photography, along with the efforts of other photographers of his time, opened the medium to new and exciting possibilities of capturing people in a way that inspired a visceral emotional reaction, specific to a viewer, while still remaining objective and informative. Some might argue that photojournalism maintains the greatest ability to inform in a dispassionately provocative manner, while creating both universal, and yet unique, sign and meaning.

Bibliography

Avedon, Richard. "American Fashion Photographer Richard Avedon - Quotes and Wisdom about Photography." Great Photography Quotes - Best Photographers Quotations. Photoquotes.com, 1997-2010. Web. June-July 2011. <http://www.photoquotes.com/showquotes.aspx?id=52>.

"Definitions of Semiotic Terms." The University of Vermont. Web. June-July 2011 <http://www.uvm.edu/~tstreete/semiotics_and_ads/terminology.html>.

Doisneau, Robert, Deke Dusinberre, Francine Derondille, and Annette Doisneau.Robert Doisneau Paris. Paris: Flammarion, 2010. Print.

Doisneau, Robert. L’Amour Sous L’occupation. 1940-1944. Photograph.

Doisneau, Robert. Le Baiser De L’Hotel De Ville. 1950. Photograph.

Doisneau, Robert. Le Regard Oblique. 1949. Photograph.

Hall, Stuart. Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices. London: Sage in Association with the Open University, 1997. Print.

Hamilton, Peter, and Robert Doisneau. Robert Doisneau: Retrospective. London: Tauris Parke, 1992. Print.

Newhall, Beaumont. The History of Photography: from 1839 to the Present. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1982. Print.

Noth, Winfred. "SRB Insights 6(2)." Computing in the Humanities and Social Sciences. SRB Archives. Web. June-July 2011. <http://projects.chass.utoronto.ca/semiotics/srb/pictures.html>.

Port, R. "Icon, Index and Symbol: Types of Signs." School of Informatics and Computing: Indiana University Bloomington. 4 Sept. 2000. Web. June-July 2011. <http://www.cs.indiana.edu/~port/teach/103/sign.symbol.html>.

Radnitzky, Emmanuel. La Violin D'Ingres. 1924. Photograph. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

Sonesson, Göran. "Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, Thinking Photography, L'acte Photographique." Psychology Encyclopedia. 2011. Web. June-July 2011.

Sonesson, Göran. "Semiotics of Photography." Thesis. Lund University, 1989.Www9.georgetown.edu. Georgetown University. Web. June-July 2011.

Tornabene, Hayden P. The Fortunes of Labor. 2011. Photograph. Castle Rock.