VERNACULAR TO NATIONAL

St. Sophia’s Cathedral, The Wooden Churches Of Galicia,

& The Ukrainian Baroque

I. INTRODUCTION

Any paper on Ukrainian architecture must be prefaced with the acknowledgment that a systematic erasure of urban centers in Eastern Ukraine is being undertaken by the Russian Federation. Within the context of similar atrocities committed against vernacular wooden synagogues1 of Western Ukraine during the Nazi invasion of 1941, the total destruction of cities like Bakhmut and Rubizhne must be understood through the lens of similar violence committed against Ukraine. The scale of the destruction in Ukraine by the ongoing invasion is comparable to every building in Manhattan being leveled four times over.

The previous colloquial designation of ‘The Ukraine’ or ‘Da Ukraine,’ where the definite article loosely translates from Russian to ‘toward,’ demonstrates a Russian strategy of undermining and delocalizing Ukraine as something loosely defined or foreign. In the context of this paper, where I will document the relationship between 17th & 18th century Galician churches and the Ukrainian Baroque, it is noteworthy that following Operation Barbarossa and the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union, the Nazi administrative state in Ukraine was divided into two components: the Reichskommissariat Ukraine and the District of Galicia. Across these regions, over five million Ukrainians were killed. The creation of a specific district to govern Galicia, based loosely on the borders of the ancient Principality of Galicia, is curious. It indicates that this place is unique within Ukraine, and that it perhaps plays a special role in Ukrainian identity, which must be understood differently.

Shaped by its participation in, and proximity to, great European Empires, this region of west Ukraine along the Carpathian Mountains would emerge as one of the most powerful principalities following the collapse of Kyivan Rus’ in 1241. The Kingdom of Galicia-Volhynia, as it would be known from 1253-1349, would fall under Polish rule in 1352. After the Union of Lublin of 1569, the Polish- Lithuanian Commonwealth would rule the region until its dissolution in 1772 when the Habsburg's would inherit the titles of the Kingship of Galicia and Lodomeria.

By 1773, Galicia’s highly diverse population of 2.6 million — centered in Lviv and Kraków consisting of Poles, Ruthenians, ethnic Jews, Germans, Armenians, Czechs, Slovaks, Hungarians, and Roma — would further shape its European character. The region’s subsequent encounter with Austro-Hungarian exploitation would further cement an individualized identity, distinct from nearby Orthodox seminary juggernauts like Kyiv and Chernihiv.

Through the lens of Galicia as a historical progenitor of Ukrainian culture, I will first document the architectural history of the St. Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv. The original 11th century construction of the cathedral by Kyivan Rus’, and its Baroque renovation in the 17th century, provide a unique framework to understand Ukrainian cultural continuity and the subsequent development of national identity. I will then catalog and analyze Orthodox timber churches built along the Carpathian Mountains in the 17th and 18th centuries.

With an examination of the features of these vernacular structures, particularly building techniques, plan layout, and roof forms, I will define the Ukrainian Baroque as a distinctly European phenomena, facilitated by church design along the Carpathians. I will argue that elements of these modest, relatively unembellished mountain structures would signal a ‘Baroquisation’ emergent in the West without Russian influence. Rural and Orthodox traditions in Galicia, coupled with the persistent legacy of Byzantine art, would directly influence the restoration of the St. Sophia. This relationship indicates that Galician vernacular architecture not only influenced the cultural development of the region, but more fundamentally the formation of a ‘modern’ Ukrainian identity.

II. THE CATHEDRAL OF ST. SOPHIA IN KYIV FROM KYIVAN RUS’ TO THE UKRAINIAN BAROQUE

The 11th century morning sun casts its golden light across the Dnipro River, revealing a monument to faith and power on the hills of Kyiv. Grand Prince Yaroslav the Wise, heir to the Christianizing mission of his father Vladimir the Great, envisioned a cathedral that would rival the greatest temples of Constantinople. The name —Sophia, God's Wisdom—echoes deliberately across the Orthodox world, drawing a spiritual lineage from the Hagia Sophia that defined Byzantine architectural achievement. Yet what emerged was no mere replica of Constantinople's wonder, but something uniquely born of this borderland between East and West.

The Orthodox Church had arrived in Kyiv just decades earlier, embraced by Vladimir in 988 as part of a calculated alliance with Byzantium. This religious conversion transformed Kyiv from a pagan trading post into a Christian capital with imperial ambitions. As Byzantine priests, icons, and liturgical practices flowed northward along the Dnipro, so too did architectural knowledge—as filtered through local tradition. The builders of St. Sophia, as Olexa Powstenko remarks, were "masters thoroughly familiar with the achievements of Byzantine art" who nonetheless "incorporated national art forms into the design and construction, erecting this impressive edifice in the Ukrainian-Byzantine style of their time.”

For Yaroslav, St. Sophia represented more than piety—it was a declaration of Kyivan Rus' arrival on the world stage. While Constantinople might claim to be the ‘New Rome’, Kyiv was positioning itself as a New Constantinople. From its commanding position, the cathedral overlooked "the administrative center, the citadel of old Kyiv and the residence of the Grand Prince of Ukraine-Rus'," becoming the crown jewel of an ambitious urban transformation. Inside its walls, Yaroslav assembled an impressive library of manuscripts, creating not just a house of worship but a center of learning and culture that proclaimed Kyiv's status as an Orthodox power in its own right.

ANALYSIS OF THE ORIGINAL STRUCTURE

Fig. 1: St. Sophia Cathedral Axonometric Original Construction

The original St. Sophia was a carefully orchestrated sequence of light and shadow, a symphony of stone that guided the faithful from earthly concerns toward heavenly contemplation. The cathedral's five-naved plan, with its central nave twice the width of the flanking ones, created a hierarchical progression toward the sanctuary. From this basic Byzantine template emerged a structure of remarkable complexity and originality, with semicircular apses to the east and galleries wrapping around the remaining three sides.

The central nave stretched 7.5 meters wide, drawing the eye upward to where arches and pendentives supported the main dome. Around this core, a series of smaller domed spaces creates what Powstenko calls "a characteristic growth of architectural volumes from the periphery toward the center." This progression of spaces culminated in the explosion of light from the thirteen cupolas overhead—a cosmological statement representing Christ surrounded by the twelve apostles.

The cathedral's construction tells a story of ingenuity and adaptation. The Byzantine opus mixtum technique—alternating layers of brick and stone—was employed throughout, but with distinctly local characteristics. The stone for these massive walls traveled a considerable distance, extracted from quarries in Volhynia in western Ukraine. Powstenko notes that while skilled craftsmen were required for brick production, "unskilled workers or even prisoners of war could be used for the extraction and transportation of stone from Volhynia." This detail reveals not just practical material sourcing considerations, but also establishes an early connection between Kyiv and the western Ukrainian lands that would later become the principality of Galicia-Volhynia. The mortar binding these materials contained crushed brick fragments mixed with lime, creating a compound "that grew stronger with time"—an apt metaphor for the cathedral itself, which would only grow in cultural significance over the centuries. Each architectural choice, from the proportion of the domes to the arrangement of internal spaces, reflected a dialogue between imported Byzantine traditions and local architectural intuition. The result was a building that, while clearly Orthodox in its liturgical arrangement, spoke in a dialect distinctly its own.

DEBATES ON INFLUENCE AND IDENTITY

The question of St. Sophia's architectural lineage has long been contentious, where scholarly arguments mask deeper questions of national identity and imperial claims. Who can claim this wonder of medieval architecture—Russia, Ukraine, or the Byzantine world? The answer depends as much on politics as on architectural evidence. Russian scholars like Professor N. Brunov acknowledge St. Sophia's uniqueness while simultaneously attempting to fold it into a Russian architectural lineage. Brunov identifies the cathedral's distinctive features—its north-south rectangular plan (rather than the square plans typical of Byzantine churches), its graduated ascension of volumes, and its thirteen cupolas that were "unknown in Byzantine architecture." Yet after these observations, he performs a remarkable intellectual sleight of hand that declares the cathedral among "the first creations of Russian architecture,” suggesting its forms led directly to Moscow's Cathedral of St. Basil the Blessed.

This Russian imperial perspective attempts to appropriate Kyivan heritage as merely the first chapter of Russian cultural history. Powstenko forcefully counters this narrative, writing: "It is true that architectural forms of the building of Grand Princely Ukraine-Rus' were imitated for a long time in Moscow, whose architecture was strongly influenced by Kyiv, but the Sobor of Basil the Blest in Moscow is an exclusively Russian architectural monument in no way related to St. Sophia.” In this view, Kyiv's influence on Moscow represents cultural transmission between distinct entities, not evidence of a singular "Russian" cultural continuity.

Other scholars, like V. Zalozets'ky, dismiss theories of local influence on St. Sophia as "an echo of the old romantic trends and their uncritical glorification of the national past." He argues that pagan wooden architecture could not have influenced Christian stone construction. Powstenko systematically dismantles this position, pointing out that Zalozets'ky "takes into consideration only the pre-Christian religious architecture of Rus', omitting lay architecture, whereas both could have left traces upon the early Christian architecture of Rus'."

Powstenko marshals considerable evidence for the influence of wooden construction on stone architecture, noting that "the Ukraine's stone architecture of the so-called Ukrainian Baroque period (17th and 18th centuries) is patterned upon Ukrainian wooden churches, the earliest examples of which date back to the Grand Princely period." He emphasizes the wooden church of St. Sophia in Novgorod dating to 989 that featured thirteen cupolas—precisely the number that would later distinguish the stone St. Sophia in Kyiv—suggesting a transfer of design concepts from wooden to stone construction.

Fig. 2: The Cathedral as viewed from the Bell Tower.

Fig. 3: Part of the western facade.

Fig. 4: Cupolas & vaults, St. Sophia.

Fig. 5: Wooden Church at Kizlov, northeast of Lviv

Fig. 6 & 7: East façade and plan of the first floor by D. Ivanov (19th c.).

Fig. 8: Part of the cluster of southwestern cupolas, St. Sophia.

Fig. 9: The Cathedral viewed from the northeast, 1970s

ST. SOPHIA AND MODERN UKRAINIAN IDENTITY

St. Sophia's significance transcended its religious function to become a symbol of Ukrainian national continuity. During Ukraine's brief period of independence from 1917-1919, the cathedral became a focus of scholarly attention, with research conducted by "the Central Committee for the Preservation of Ancient Monuments and Art and, from 1918 on, by the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences.” This scholarly interest reflected the cathedral's importance to emerging conceptions of Ukrainian national identity.

The cathedral's symbolic power made it a target during subsequent conflicts over Ukrainian sovereignty. During the Russian Bolshevik attack on Ukraine in January 1918, St. Sophia suffered significant damage from artillery fire, despite the Ukrainian Democratic Republic declaring Kyiv an open city "in order to preserve its architectural monuments.” This attack on Ukraine's cultural heritage paralleled the political assault on its independence—both aimed at erasing distinctive Ukrainian identity.

Under Soviet rule, the cathedral's religious function was suppressed. In 1934, religious services were prohibited as Soviet authorities characterized the cathedral as "not only a center for the religious deception of the masses, but also a nest of counter-revolutionaries." Official Soviet tour guides explicitly criticized the cathedral for supporting "the Ukrainian bourgeoisie, the Central Rada" during the revolutionary period. This repression stemmed from the cathedral's association with Ukrainian national aspirations—the Soviet authorities understood, perhaps better than many scholars, that St. Sophia represented not just religious tradition but Ukrainian cultural distinctiveness.

Despite centuries of political turmoil, St. Sophia has endured as what Powstenko calls a "living symbol" and "The Indestructible Wall" for the Ukrainian people. Its survival through "nine hundred years of the land and the people of Ukraine-Rus'" and "a thousand years of sackings, violence and desecrations" testifies to its central place in Ukrainian cultural consciousness. Like the nation itself, St. Sophia has been shaped by influences from east and west, has endured periods of destruction and renewal, and yet has maintained a continuous identity across the centuries.

The architectural history of St. Sophia Cathedral offers us a window into Ukrainian cultural formation at this nexus of East and West. From its origin as a creative adaptation of Byzantine models to its transformation through the Ukrainian Baroque, the cathedral embodies Ukraine's distinctive cultural synthesis. The architectural history of St. Sophia significantly challenges imperial narratives that would subsume Ukrainian cultural achievements within a Russian or generic "East Slavic" framework. The debates over St. Sophia's architectural lineage reveal the political stakes of cultural attribution, with scholars like Brunov attempting to claim the cathedral for a Russian architectural lineage while Powstenko insists on recognizing its distinctly Ukrainian character.

The cathedral's Baroque transformation in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, made possible by Ukraine's connections to European cultural currents flowing through the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, demonstrates how architecture became a medium for expressing cultural positioning. By adopting and adapting European Baroque elements—particularly the distinctive pear-shaped domes —Ukrainian architects created a visual language that proclaimed their European orientation while maintaining their Orthodox heritage.

As I will discuss in the next section, this linkage with the Polish- Lithuanian Commonwealth was made possible by Carpathian craftsmen who readily implemented Baroque themes in their vernacular structures. A similar processes of cultural synthesis manifested in these structures, creating architectural expressions that would eventually influence the Ukrainian Baroque exemplified in St. Sophia's renovation. These wooden churches, built in the mountains of Galicia and Volhynia—the very regions that supplied stone for St. Sophia's construction—represent a crucial progenitor of Ukrainian architectural identity.

III. VERNACULAR WOODEN CHURCHES OF GALICIA-VOLHYNIA

ORTHODOX CHRISTIANITY ALONG THE CARPATHIAN MOUNTAINS

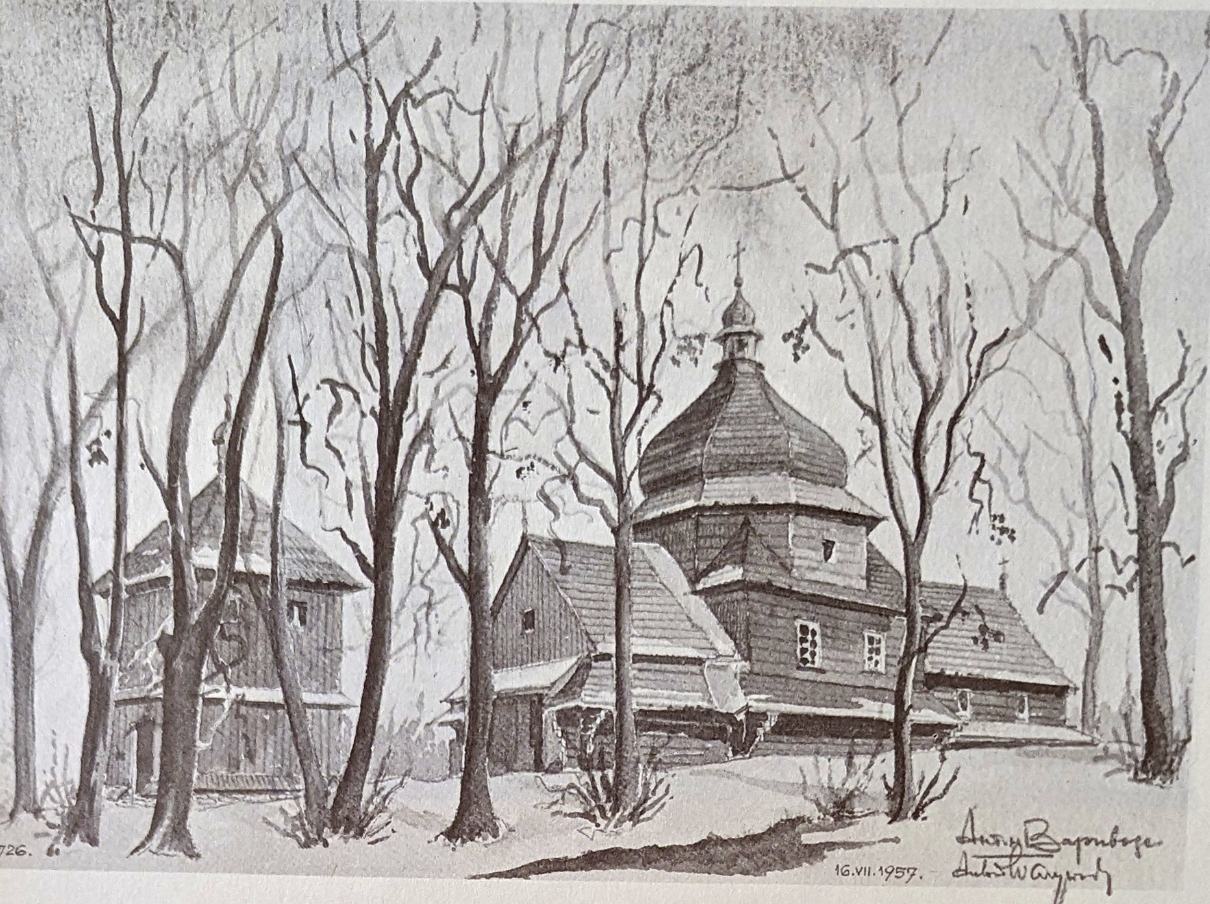

Fig. 10: Derevach (Derewacz), Monastery - 1680 - Деревач, монастир

The story of wooden church architecture in the Carpathian Mountains begins with the spread of Orthodox Christianity into this mountainous borderland. Following the Christianization of Kyivan Rus' in the late 10th century, the Orthodox faith gradually penetrated the Carpathian highlands, bringing with it liturgical requirements that would shape architectural forms for centuries on. Unlike the monumental stone cathedrals of urban centers like Kyiv, these remote mountain communities developed a distinctly vernacular approach to sacred architecture, one that responded to local materials, climate conditions, and the unique cultural identity of the mountain-dwelling peoples.

The Carpathian region, straddling what is today southeastern Poland, eastern Slovakia, western Ukraine, and northern Romania, has witnessed a complex religious history. As David Buxton notes, churches in this area "belonged to one of three religious denominations: Roman Catholic, Greek Catholic, or Orthodox." This religious diversity was further complicated by the Union of Brest in 1596, when "west Ukrainian ecclesiastics, at the Synod of Brest, concluded the union with the Church of Rome, thus establishing the first of the Uniate churches." This event created a division within the Orthodox communities of the region, with some accepting papal authority while maintaining Eastern liturgical practices (becoming Greek Catholic or Uniate), while others remained Orthodox.

Despite these theological divisions, the architectural traditions remained remarkably consistent, as both Orthodox and Greek Catholic churches maintained the same liturgical requirements and spatial organization. John Hvozda observes, "perhaps the most characteristic feature of all Ukrainian wooden churches is the clearly discernible three-fold subdivision of the plan into narthex, nave and chancel." This tripartite division, reflecting the spiritual journey from the earthly realm (narthex) through the world of the faithful (nave) to the divine mystery (chancel), would become a defining characteristic of Carpathian sacred architecture regardless of specific denominational affiliation.

THE PEOPLES AND BUILDING METHODS OF THE CARPATHIANS

The wooden churches of the Carpathians were built by distinct ethno-cultural groups that Buxton identifies as "three different sections of the hill-dwelling Ukrainians or Ruthenians who form the majority of the population." These groups—the Boykos, Hutsuls, and Lemkos—each developed distinctive architectural styles that reflected their particular cultural sensibilities, geographic circumstances, and historical influences.

The origins of these mountain communities remain somewhat contested. According to some accounts, they descended from "successive waves of nomad herdsmen who, arriving from the south from the fifteenth century onwards, washed up against the Carpathians and tended to settle there." This movement was part of the broader Vlakh or Wallachian migration that brought diverse elements, including "residual groups of the ancient Thracians" and "Slav elements from the Balkans." Over time, these groups assimilated with local Ukrainian populations, creating distinctive cultural enclaves throughout the Carpathian highlands.

Fig. 11: Systems of corner-jointing

What united these diverse communities was their masterful approach to wooden construction. Unlike Western European timber architecture, which relied primarily on post-and-beam construction, Carpathian builders employed the "blockwork" or "log-cabin" (zrub) technique. Hvozda explains that this method "consisted of placing timbers horizontally in successive layers and jointing them at the corners to form load-bearing walls."

This technique created structures of remarkable durability and ingenuity without the use of nails or metal fasteners. Unlike Northern Russian preparation, where building proceeded with whole round logs untrimmed, Carpathian builders carefully selected and prepared timber elements. Buxton notes that "in the Ukraine, in Rumania and the whole Carpathian area the builders were more particular, each log being flattened off at least on its inner surface, often on all four sides." Hvozda elaborates that "only timber of the highest quality was used in the construction of churches," with spruce, pine, fir, and beech being the most common species employed.

Rather than using round logs, Carpathian builders typically worked with "squared logs (brusy), split or half-round logs (plenytsi), or boards.” A distinctive aspect of this construction method was its holistic relationship between interior and exterior. Hvozda emphasizes that "a characteristic feature of this type of wooden architecture is that the total interior space, including the interior space of roofs and towers, corresponds exactly to their exterior. There are no false ceilings, no internal columns, no diagonal braces to strengthen towers." This created a profound spatial integrity in which "the shell of the building is at the same time its own structural support."

The builders' deep understanding of their material allowed them to create structures of surprising complexity. Buxton describes how Boykian carpenters "were masters of all the subtleties of their traditional techniques. Walls could be made to converge, and then to rise vertically again; they could be inclined inwards at an increasing angle until they met in the middle line in the form of a vault; or the basic rectangle could be converted at will to an octagon, rising vertically in the form of a drum to be crowned by its broad-based dome." All this was accomplished using only basic tools—"with the axe alone, not even saws being available."

The Carpathian climate, with its heavy precipitation of over 1000 mm annually, necessitated specific adaptations. To protect the wooden structures from moisture, builders developed several ingenious solutions. Hvozda describes how "the exteriors of churches were covered with shingles or board sheathing" not only for practical purposes, but also as decorative elements that created "aesthetic effects of lights and shadows."

Perhaps most distinctively, Carpathian churches featured "wide roof overhangs or arcades (opasannia), generally supported on brackets or consoles built up of projecting wall timbers." These galleries surrounded the entire church and served both to protect the foundations and lower parts of the structure from water damage and to enhance "the general artistic composition of the structure."

DISTINCTIVE STYLES: BOYKOS, HUTSULS, AND LEMKOS

Fig. 12: Boyko ground and roof plans.

CHURCHES OF THE BOYKOS

The Boykos, inhabiting the central Carpathian region, created perhaps the most conservative of the three architectural traditions. Their churches adhered strictly to the tripartite plan with "the pronaos or narthex (also called babinets or 'women's church'), the naos and (beyond the iconostasis) the sanctuary." The defining characteristic of Boyko churches was the dominance of the middle dome over the sanctuary and narthex, with "the central space or naos [being] a broader element in the plan than either the narthex or the sanctuary."

Visually, Boyko churches created their effect through the distinctive stepped silhouette of their roofs. Hvozda observes that "the silhouette of many Carpathian churches resembles a cascade of narrow horizontal bands," with the distances between recesses (zalomy) being quite short, "sometimes as little as 2 or 3 layers of timbers." This created a distinctive terraced profile that harmonized with the surrounding mountain landscape.

Buxton emphasizes the Boykos' commitment to traditional construction methods: "With few (and late) exceptions the Boyks remained faithful to the old log or blockwork technique which was the common legacy of all the Slavs." This conservatism extended to their resistance to Baroque influences. While they eventually adopted bulbous domes, Buxton notes that "no real Baroque features penetrated their architecture, except for internal fittings, especially the iconostasis."

CHURCHES OF THE HUTSULS

The Hutsuls, inhabiting the eastern Carpathians, developed the most distinctive plan configuration among the three groups. Unlike the linear tripartite arrangement favored by their neighbors, Hutsul churches typically featured a cruciform plan. As Buxton notes, "These Hutsul churches, unlike those of the Boyks and Lemks, are nearly always of cruciform plan with five divisions instead of three."

Hvozda elaborates that these cruciform churches could be "composed of either five, seven (rare) or nine parts, having one, three, five, seven or nine towers.” The reasons for this preference remain uncertain. Buxton speculates that it might reflect "possible Byzantine antecedents," greater prosperity allowing for "the more complex plan," or more concentrated settlements requiring "bigger churches." Regardless of its origins, this cruciform arrangement created a more centralized spatial experience than the linear progression of Boyko and Lemko churches.

Fig. 13: Yezupol, near Ivano-Frankovsk. Hutsul church with five domes, eighteenth century. (Left) Knyazhdvor, near Kolomya. Five-domed Hutsul church of 1778. (Right)

Hutsul domestic architecture also reflected distinctive cultural patterns. Hvozda describes the Hutsul osedok or homestead as "an independent closed ensemble of living and farm buildings joined by a high fence (grazhda) around a courtyard" that "forms a kind of fortress." This self-contained compound "effectively protected its inhabitants from enemies, wild beasts and inclement weather," suggesting it might once have been common throughout Ukraine but survived only in "the more remote regions of the Carpathians." The defensive character of Hutsul settlements points to the precarious historical position of these mountain communities amid competing imperial powers.

Fig. 14: Turyans'k (Turiansk), Church - 1615 Турянськ, церква

CHURCHES OF THE LEMKOS

The Lemkos, occupying the western Carpathian regions extending into what is now southeastern Poland and eastern Slovakia, developed the most innovative and evolutive of the three architectural traditions. As Buxton observes, "It is a fact not fully explained that the Lemks (or Lemkians or Lemki), in contrast to their neighbors and kinsmen the Boyks, were quite open to new ideas and influences." This openness resulted in a distinctive church design characterized by a tall western tower that "dominates the whole composition.”

This receptivity to external influences can be attributed to the Lemkos' geographic and cultural position. Buxton notes that they "have been in contact, to the south, with Transylvania and Hungary" and extend "much further west than those of the Boyks, both on the Slovak and the Polish side of the hills... reaching almost as far west as the town of Nowy Sacz (Novy Sonch) south-east of Kraków, and thus have long had relations with the Catholic Poles." This exposure to diverse architectural traditions, combined with the region's incorporation into the Austro-Hungarian Empire throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, created fertile conditions for architectural innovation. Buxton emphasizes the crucial role of Lemko mobility and cultural openness in their architectural innovation. He writes that "Lemk master craftsmen... could have wandered far enough afield to see with their own eyes both Gothic and Baroque churches in Poland, in Hungary proper and in the cities of the Transylvanian Germans. They would certainly have seen the earlier attempts of their neighbors, the Rumanian villagers of Maramures, on the Transylvanian borders, to interpret these churches in timber." This direct exposure to diverse architectural traditions allowed Lemko builders to synthesize elements from multiple sources. Buxton further notes: "I suspect that this contact was particularly fruitful, but they were seemingly impressed above all by the charms of the Baroque tower which was to become a special feature of their own style."

Unlike the rest of the church, which maintained the traditional blockwork construction, these western belfries employed "framed construction" techniques. In the central and eastern Lemko regions, these towers were "mounted, Rumanian fashion, on the horizontal beams of the narthex ceiling." This hybrid approach—combining traditional horizontal blockwork with vertical frame construction—demonstrates the Lemkos' creative synthesis of diverse building traditions.

Fig. 15: Drohobych (Drohobycz), Church - 1612 - Дрогобич, церква

Fig. 16: Koman'cha (Komancza), Syanik, Church - 1676 - Команьча, Сянік, церква

Fig. 17: Dovhe (Dothe), Stryi, Church - 1645 - Довге (Долге), Стрий, церкваа

THE LEMKO CONTRIBUTION TO UKRAINIAN BAROQUE

The Lemkos' openness to architectural innovation made them particularly important in the development of what would become known as the Ukrainian Baroque. Buxton's analysis of their role is unequivocal: "Both Ukrainian and Russian scholars have generally agreed that the Ukrainian wooden style, which reached the peak of its development as late as the 17th and 18th centuries, was a potent influence upon the Ukrainian Baroque evolving at the same time." This suggests that rather than merely imitating stone architecture, these wooden churches actively contributed to the development of an emerging distinct Ukrainian style.

Fig. 18: Chertezh (Czertez), Syanik, Church — 1726 - Чертеж, Сянік, церква

Buxton offers a detailed analysis of how Baroque elements were integrated into Lemko wooden architecture, noting that "wherever bulbous shapes appear in these more western regions, where Russian influence is unlikely, one sense[s] the onset of the Baroque." He describes these elements in detail: "Domes of this form, commonly on stalks rather than drums, and sometimes accompanied by odd little disks or aprons above or below, often occur in this area as a capping to pyramidal roofs and towers.

They mark a stage in the 'Baroquisation' of the style, yet may accompany modest towers and simple unstepped roofs as at Korejovce." This gradual integration culminated in a full synthesis: "With the heightening of the Western belfries the full-blown Baroque takes over and we find all three divisions of the church finished off with slender dome-cum-lantern pinnacles, conferring that unity on the building."

This architectural evolution coincided with the broader cultural changes following the Union of Brest. Buxton observes that "such contacts may well have been stimulated by a common allegiance to the Pope after the western Ukrainian and Trans-Carpathian Churches accepted the suzerainty of Rome (1596 and after)." The Lemkos' position within the sphere of Polish-Lithuanian influence facilitated their exposure to Western European architectural ideas, which they creatively adapted to local building traditions.

The resulting synthesis—with its distinctive silhouette of three towers dominated by a western belfry, all crowned with bulbous domes—became a visual expression of Ukrainian cultural identity at the crossroads of East and West. Unlike the more conservative Boyko churches, which maintained closer ties to traditional Orthodox forms, or the distinctive cruciform plans of the Hutsuls, the Lemko churches embodied a cultural openness that would come to characterize Ukrainian architecture more broadly.

This architectural innovation paralleled Ukraine's broader cultural positioning. As Buxton notes, "the Baroque style, propagated above all [by] the Jesuits, crept in through these western marches. The omnipresence of Catholic Poles as a governing class ensured it, but the style was eventually adopted with enthusiasm by the Ukrainians themselves." This willing embrace of Baroque aesthetics, filtered through local sensibilities and building traditions, produced a distinctively Ukrainian architectural language.

FROM VERNACULAR TO NATIONAL: THE LEGACY OF WOODEN CHURCHES

The significance of these vernacular churches extends beyond their local contexts. Buxton observes that the contemporaneous maturation of both the Ukrainian Baroque and the wooden style implies a profound link between vernacular and national architectural forms. This linkage suggests a bidirectional flow of influence—not only did monumental masonry architecture influence wooden vernacular forms, but the vernacular traditions themselves shaped the development of the Ukrainian Baroque seen in urban centers. The timing of this architectural flowering is politically significant. Buxton notes that "the unique later developments of Ukrainian wooden architecture... took place in the 17th and the first 60 years of the 18th century, while the Ukraine still clung precariously to some measure of independence."

Fig. 19: Petryliv (Petrytów), Tlumach, Church - 1786 - Петрилів, Тлумач, церква

Lev Maciel notes that Ukrainian cultural activity dramatically decreased under the rule Catherine II the Great (1762–1796). Catherine's abolishment of the Cossack Hetmanate further eroded Ukrainian autonomy as buildings progressively lost their identity and began to blend with Russian architecture by the end of 18th century.

After this period, "though some fine churches were still erected, they showed no originality of design, while the general tendency was one of reliance and decay." This correlation between architectural creativity and political autonomy suggests that these wooden churches represented more than mere buildings—they were expressions of cultural identity during a period of contested sovereignty.

The wooden churches' influence on the restoration of St. Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv creates a direct link between these vernacular traditions and the monumental architecture discussed in the previous section. The distinctive bulbous domes that crowned St. Sophia after its Baroque renovation—which Powstenko described as "the pear-shaped baroque form characteristic of the Ukraine"—find their precedents in the wooden churches of the Carpathians, particularly those of the Lemko regions where Western Baroque influences were most readily absorbed and adapted.

The architectural scholar Josef Strzygowski even proposed a more radical theory about the historical significance of Ukrainian wooden architecture. According to Buxton, Strzygowski believed that "Ukrainian wooden architecture had played a specific role" in architectural history "by reproducing, in wood, the Persian dome over a square base" and thus making "possible the transmission of this feature to the western world." While Buxton remains skeptical of this grand claim, preferring to see Ukrainian wooden churches as connected primarily to "the ancestral wooden architecture of the old Slav homeland," the debate itself demonstrates the cultural significance attributed to these seemingly humble structures.

VERNACULAR FORMS AND CULTURAL IDENTITY

Fig. 20: Church of the Archangel Michael, western aspect.

The wooden churches of the Carpathians, with their distinctive silhouettes rising against mountainous landscapes, represent a profound synthesis of spiritual needs, material constraints, and cultural identity. As Hvozda observes, these structures achieved "an organic relationship between external appearance and internal construction, a subordination of individual parts to the general ensemble," and "a building technique that defines the structure itself."

Their forms developed not through academic theory but through generations of practical wisdom and master craftsmen that responded intimately to their natural environment and cultural aspirations.

The three main stylistic traditions—Boyko, Hutsul, and Lemko— each expressed different aspects of Ukrainian cultural positioning. The conservative Boyko churches maintained closest ties to traditional Orthodox forms. The cruciform Hutsul churches created centralized spaces that echoed Byzantine models while responding to local security needs. And the innovative Lemko churches, with their prominent western towers crowned by bulbous domes, embodied the creative synthesis of Eastern and Western influences that would come to characterize Ukrainian Baroque architecture more broadly.

Most significantly for this analysis, the Lemko churches of western Galicia-Volhynia demonstrate how this region's proximity to Polish-Lithuanian territories facilitated the transmission of Western European architectural ideas into Ukrainian cultural expression. The distinctive bulbous domes, that would later crown St. Sophia Cathedral after its Baroque renovation, trace their lineage to these vernacular experiments in the Carpathian highlands. Far from being mere provincial curiosities, these wooden churches represent a vital link in the formation of Ukrainian architectural identity—one that drew creative inspiration from both East and West while remaining rooted in local traditions and materials.

Religious context that fostered this architectural creativity in Galicia was remarkable. As Paul Robert Magocsi notes, "by the late sixteenth century, Galicia, and especially L'viv, became the most important center of religious and intellectual life for all Orthodox Rus' lands within Poland." The L'viv Stauropegial Brotherhood, who were granted special status in 1589 that made it answerable only to the Patriarch in Constantinople rather than local bishops, became a model for similar organizations throughout Ukrainian and Belarusian lands. This religious and intellectual leadership positioned Galicia at the center of developments concerning church unity, making it "not surprising that the controversial question of church unity was related in large measure to developments in Galicia."

The central role of the church in maintaining Ukrainian identity during Polish rule cannot be overstated. Magocsi observes that "because they lived in a Polish state, [Ukrainians] had lost their traditional elite social strata during the process of polonization, and were deprived of a middle class owing to their exclusion from legal privileges enjoyed by other urban groups. [Thus] the Ukrainians of Galicia maintained a distinct cultural and national identity primarily because of their membership in the Orthodox Rus' and later Uniate church."

Fig. 21: Chotyniec, Rzeszów province, Poland. Church originally built 1613.

Fig. 22: Drogobych, south-west of Lviv. Seventeenth-century church of St George from the north.

Magocsi concludes that "in many ways, the history of Ukrainians in Galicia between 1387 and 1772 is the history of their Orthodox and Uniate churches.”88 This religious cultural foundation fostered during the Era of Polish rule supported significant artistic creativity, particularly in architecture and painting. Consequently these artistic achievements "provide a fuller understanding of the life-style of the secular and religious cultural elite in Galicia."89 The wooden churches of the Carpathians represent the vernacular expression of this broader cultural flourishing—a testament to the deep linkages between religious identity and artistic creativity in these remote mountain communities.

The vernacular wooden churches of Galicia-Volhynia, particularly those built by the Lemkos on the western slopes of the Carpathians, represent a vital link in the formation of Ukrainian architectural identity. Their openness to innovation, combined with their masterful adaptation of new ideas to traditional building techniques, created a visual language that would influence Ukrainian architecture far beyond the Carpathian highlands, ultimately contributing to the distinctive Ukrainian Baroque style that transformed monuments like St. Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv.

These humble wooden structures, built by anonymous master craftsmen in remote mountain villages, thus played a crucial role in the broader story of Ukrainian cultural formation—a story in which Galicia served as a vital crossroads between Eastern and Western influences, creating a synthesis that was neither simply Eastern nor Western, but distinctively Ukrainian.

IV. CONCLUSION: AT THE CROSSROADS OF EAST AND WEST

Fig. 23: Berezhany (Brzezany), Church - 1712 - Бережани, церква

The architectural heritage of Ukraine reveals a profound story of cultural formation at the nexus of Eastern and Western influences. From the monumental St. Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv, to the humble wooden churches nestled in the Carpathian highlands, Ukrainian architecture embodies a distinctive synthesis that defies simplistic categorization.

Instead, these structures articulate a uniquely Ukrainian cultural voice that emerged through centuries of creative adaptation and resilience. St. Sophia Cathedral stands as a testament to this cultural continuity as its original 11th-century construction represented an early creative adaptation of Byzantine models, incorporating local building traditions and materials—including stone from Volhynia.

This early connection between Kyiv and these western lands foreshadowed the later cultural exchanges that would shape Ukrainian architectural identity. The cathedral's transformation during the late 17th and early 18th centuries reflected Ukraine's emerging orientation toward European cultural currents flowing through the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

The vernacular wooden churches of the Carpathians provide the crucial missing link in this architectural evolution. Built by master craftsmen of the Boyko, Hutsul, and particularly Lemko communities, these structures demonstrate an extraordinary synthesis of spiritual requirements, ecological adaptation, and cultural positioning. The craftsmen's profound understanding of their material and local ecology allowed them to create structures of remarkable durability and sophistication using only axes and basic tools.

Their ingenious solutions to the challenges of the mountain climate, including wide protective galleries and decorative shingle patterns, reveal both practical wisdom and aesthetic sensitivity. Most significantly, the Lemko churches of western Galicia-Volhynia demonstrate how this region served as a vital conduit for architectural innovation. Their geographical position near Polish territories and their cultural openness facilitated the absorption and adaptation of Western architectural ideas, particularly Baroque elements. The distinctive bulbous domes that would later crown St. Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv trace their lineage to these vernacular experiments in the Carpathian highlands. Far from being mere provincial curiosities, these wooden churches represent a vital link in the formation of Ukrainian architectural identity.

Fig. 24: Cherhanivka (Czerhanówka), Kolomyya, Church - 1864 — Черганівка, Коломия, церква

The religious context of Galicia further enhanced its role in Ukrainian cultural formation. As Magocsi notes, "by the late sixteenth century, Galicia, and especially L'viv, became the most important center of religious and intellectual life for all Orthodox Rus' lands within Poland." This religious foundation fostered significant artistic creativity, particularly in architecture, that would eventually influence developments throughout Ukrainian lands. The temporal alignment between the flowering of vernacular wooden architecture and Ukraine's period of relative autonomy in the 17th and early 18th centuries is not coincidental.

This architectural creativity corresponded with a period of Ukrainian cultural assertion before the Russian imperial absorption that began under Catherine II. The architectural vocabulary that developed became visual markers of Ukrainian cultural distinctiveness at a time when political autonomy was increasingly threatened.

The architectural legacy examined here challenges imperial narratives that would subsume Ukrainian cultural achievements within Russian or generic "East Slavic" frameworks. The distinctive features of Ukrainian architecture—whether in the monumental St. Sophia Cathedral or in vernacular wooden churches—reflect a cultural identity formed through creative engagement with diverse influences. Ukrainian architecture, from the Byzantine-influenced Cathedral of St. Sophia to the Baroque- influenced wooden churches of the Carpathians, demonstrates how a nation positioned between powerful neighbors can develop a distinctive cultural voice through selective adaptation rather than mere imitation.

This architectural heritage presents a visual argument for understanding Ukrainian culture on its own terms—neither as a subset of Russian culture nor as a peripheral extension of European traditions, but as a distinctive synthesis formed at the dynamic intersection of East and West. The continued significance of these structures in Ukrainian cultural consciousness testifies to their role not merely as historical artifacts but as enduring symbols of national identity and cultural resilience.