BOSCO VERTICALE

TECHNOLOGICAL SPECTACLE AND THE LIMITS OF NEOLIBERAL GREEN ARCHITECTURE

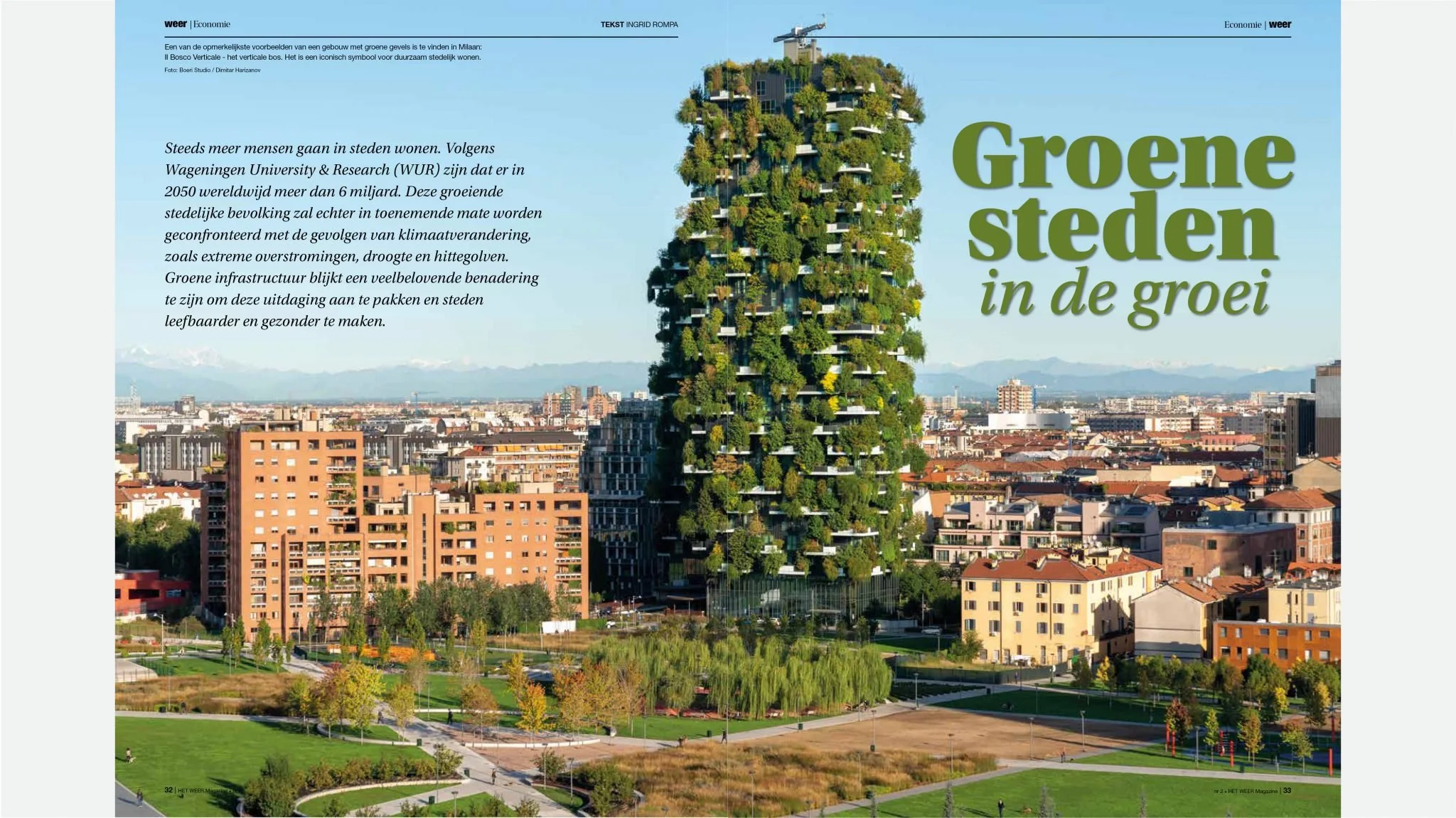

Stefano Boeri Architetti's Bosco Verticale opened in 2014 promising radical transformation: 800 trees, 4,500 shrubs, and 20,000 plants that reimagined luxury housing as vertical parkland.[1] The press celebrated as critics heralded a new era of climate responsive architecture. Yet beneath this verdant spectacle persisted a vacuous and hollow promise. Bosco Verticale's green facade concealed its extensive cost and proximity to luxury as precondition for its existence.

Charlotte Malterre-Barthes describes these tree-adorned skyscrapers as “parading technological solutions,” which further commodify nature into the built environment through growth-oriented spatial production.[2] Bosco Verticale functions as sophisticated ecological theater: architecture that performs environmental consciousness while advancing the economic and spatial logic of neoliberal development. Where eco-brutalism seeks to integrate raw materiality with sustainable restraint, Bosco Verticale fetishizes technology, privatizes ecology, and transforms sustainability into a luxury commodity.

BUILDING AS APPLIANCE: FETISHIZING TECHNOLOGICAL MEDIATION

The project began with Milan's Porta Nuova development, one of the largest, densest and most complex urban renewal operations in the recent history of Milan.[3] In 2006, Texas-based Hines acquired massive ex-industrial land adjacent to Porta Garibaldi station. The smallest plot, Isola-Lunetta, became Bosco Verticale's site, but only after demolishing the Stecca degli Artigiani, an occupied factory serving as headquarters for anti-gentrification resistance in the working-class Isola neighborhood.

Hines CEO Manfredi Catella invited Boeri Studio "without a competition process" to design the masterplan, positioning Stefano Boeri as "mediator between the developer and the users of the Stecca."[4] Participatory initiatives with local activists proposed preserving the cultural space and public lawns. Boeri's masterplan "foresaw the demolition of the Stecca and the privatization of its two public lawns."[5]

The token compensation, a smaller "Stecca 3.0" built elsewhere, dismissed community alternatives through what critic Davide Tommaso Ferrando describes as "a strategy to legitimize decisions that had already been made.”[6] This erasure exposes sustainability's function in neoliberal urbanism. Projects likeBosco Vertical generate existential purpose for construction disciplines while business runs as usual.[7] When ecological narrative sanctifies displacement, this vertical forest serves as symbolic compensation for destroyed ground-level community space, translating social destruction into aesthetic redemption through technological prowess.

Official narratives transform Bosco Verticale from architecture into technical apparatus. The project is consistently described through measurable outputs: CO2 absorption, oxygen production, temperature reduction, as if it were "not architecture but a gigantic technical appliance."[8]

Much in the spirit of Corbusier's 'a machine for living', promotional materials emphasize significant benefits in terms of fine dust and CO2 absorption, oxygen production, optimization of water management, reduction of noise pollution, recasting residential towers as environmental services machines.[9] This reframing is deliberate. It positions the building within what Malterre-Barthes identifies as capitalism's "techno-fix" parallel to the spatial fix: perpetually seeking crisis resolution through technological escalation rather than fundamental restructuring.[10]

The maintenance systems expose this artificiality. The "Flying Gardeners,” professional tree climbers who abseil down the towers twice yearly with ropes, helmets, and safety harnesses, have become marketing signatures. Their theatrical presence reinforces this ecology’s dependence on technological mediation.[11] The irrigation system further exemplifies this dependency: centralized, digitally monitored, managed remotely at the condominium level, ensuring "that each pot has the right amount of water" through systems drawing on recycled greywater, powered by rooftop solar panels.[12]

While presented as sustainable innovations, these systems reveal an architecture unable to function without intensive technological intervention. Bosco Verticale mimics nature's appearance, all the while demanding extraordinary infrastructure to maintain that mimicry. The building becomes not an integration of human and natural systems but a demonstration of technology's capacity to simulate ecological processes.

PRIVATIZING ECOLOGY: SUSTAINABILITY AS CLASS PRIVILEGE

The project’s economic structure exposes Bosco Verticale's neoliberal logic most starkly. Current market prices range from €15,000–20,000/m², with one-bedroom units at €1.3 million and four-bedroom apartments at €5.5 million—nearly double the surrounding area's €9,000/m² average.[14] Service charges including essential tree maintenance "can reach up towards €3,000/month."[15] These figures are not incidental. They reveal how environmental benefits become premium commodities accessibleonly to Milan's wealthy elite.

Official descriptions make this privatization explicit: "Each apartment hosts at least 2 trees, 8 shrubs, and 40 plants for each tenant, allowing for proximity to the green component and the related physical and psychological benefits."[16] Plants become amenities "hosted" by apartments, their benefits quantified like square footage. The greenery functions as common asset, shared between all the tenants, yet this commons requires entry prices excluding working-class residents displaced by development.[17] A project claiming to address urban environmental challenges through biodiversity and improved air quality restricts these benefits by wealth, creating stratified engagement with ecological privilege.

The contrast with Stefano Boeri Architetti's later Trudo Vertical Forest in Eindhoven illuminates this position. Social housing units rent for €630 monthly; construction costs stayed at €1,200/m² through prefabrication.[18] The Eindhoven project proves vertical forests need not be exclusive. The Milan towers' business model depends precisely on exclusivity, creating what eco-brutalism theory would recognize as false integration: green walls, solar panels, rooftop gardens, tree-adorned balconies functioning as typical features of greenwashing rather than spatial reorganization. [19]

MATERIAL CONTRADICTIONS: GREEN SPECTACLE'S ECOLOGICAL COST

We may justifiably ask whether the environmental benefits of any construction justify the material footprint. While Arup associate director Luca Buzzoni claims embodied carbon is "only 1% higher than that of a standard building of the same size," this comparison misleads.[20] It measures towers against conventional luxury construction, rather than genuinely sustainable alternatives or against not building at all. As Malterre-Barthes observes, "global forecasts predict that material consumption will double by 2060, with one-third of this increase attributed to construction.”[21] The abandoned rooftop wind turbines reveal technological selection criteria.

Originally proposed to produce renewable energy and make "the buildings speak of a new sensibility," they were scrapped due to high-altitude wind speed concerns, replaced by photovoltaic panels powering only irrigation pumps and maintenance cranes.[22] This substitution exemplifies the approach: technological systems adopted not for genuine ecological efficacy but for their capacity to signal environmental consciousness. A resultant architecture consumes vast concrete and steel quantities to create sustainability's appearance, while actual energy and resource flows depend on continuous technological input.

(Left to Right): Bosco Verticale (Milan) → WOHA’s Oasia Hotel (Singapore) → Tao Zhu Yin Yuan (Taipei)

While official narratives emphasize that systems utilize groundwater and recycle the building's greywater, specific consumption figures remain conspicuously absent.[23] For a project housinghundreds of trees in elevated planters subject to wind and sun exposure, irrigation demands must be substantial. This information withholding suggests actual resource use contradicts green narratives. Similarly, while Stefano Boeri claims air conditioning is almost never used during the summer because trees' shade reduces internal temperature by 2-3°C, apartments are nevertheless equipped with air conditioning despite natural cooling elements.[24]

Claims that vegetation absorbs roughly 14 tons of carbon dioxide and 57 tons of pollutants each year while also producing about 9 tons of oxygen requires contextualization.[25] These figures, impressive in isolation, pale against construction's embodied carbon. More significantly, they measure Bosco Verticale against absence rather than alternatives.

As Ferrando notes, promotional materials claim the project offers benefits "equivalent to about five hectares of parkland on flat land, but concentrated on an area of approximately 1,000 square meters."[26] Yet actual parkland provides benefit without requiring sophisticated irrigation systems or luxury apartment sales to justify existence. The claimed efficiency of achieving parkland benefits on "fifty times less" area only makes sense within frameworks already accepting maximum urban densification as inevitable and desirable.[27]

BEYOND CHECKLISTS: A FAILURE TO TRANSFORM DWELLING

The project operates according to LEED certification logic: sustainability as checklist of discrete elements, trees (biodiversity), solar panels (renewable energy), greywater recycling (water conservation), layered onto conventional luxury residential typology.

As Ferrando observes, "if the 'forest' were removed from the proverbial 'vertical forest', what would remain is a banal residential complex with standard architectural features."[28] This is not merely aesthetic critique. It reveals how thoroughly the project separates green components from fundamental spatial organization and material reality.

Malterre-Barthes identifies this pattern: "Architectural greenwashing will boast the use of sustainable technologies and green certifications but will not consider the entire lifecycle of the structure, including construction material sourcing, energy consumption, and eventual demolition."[29]

Zhongshan Football Stadium in Taipei, Taiwan - Transformed into Urban Farm

Bosco Verticale exemplifies this selective accounting. Apartment layouts were overseen by Boeri Studio, but interiors were curated by COIMA Image, the design arm of the real-estate company, exhibiting stark separation between ecological performance and spatial experience.[30] Despite panoramic corner windows designed to maximize the relationship between inside and outside, the structural system supporting trees creates "awkward technical recesses inside" rooms.[31] The double-height glazed ground-level facade, while providing direct relationship to the public space, remains "reminiscent of the corporate architecture that populates the neoliberal cityscape of Porta Nuova."[32] The interiors possess what Ferrando describes as "slick, corporate flavor" compromising "the whimsical quality of the Bosco Verticale."[33]

The forest exists as exterior ornamentation, not as principle organizing spatial experience or daily life. Official descriptions inadvertently confirm this when noting the central distribution core moved to the perimeter, a reduction in the amount of living space exposed on the facade, to ensure "natural light and high-quality communal and shared spaces."[34]

Residents do not tend gardens, participate in cultivation decisions, or integrate plant care into daily routines. They are explicitly prohibited from modifying greenery in the building which is “owned by everyone and cannot be modified, removed, or replaced by the individual apartment tenants."[35] This arrangement transforms inhabitants into spectators of ecology rather than participants as they consume view and air quality benefits, while actual relationship to living systems remains mediated, managed, fundamentally passive.

Simona Pizzi who lives in the tower remarks that, "It doesn't feel like we're living right in the middle of busy Milan, where everything goes quite fast."[36] By not transforming urban dwelling but providing insulation from it, Bosco Vertical fails to address its fundamental conceit. The vertical forest creates retreat, sanctuary, escape. It does not reimagine how humans inhabit cities collectively, rather it offers privileged individuals private refuge from urban intensity.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

Bosco Verticale emerged from a deep and fundamental concern over the effects of global warming, offering architecture as technical solution to ecological crisis.[37] A decade later, with Milan facing judicial investigations into the alleged system of corruption behind the dramatic transformation of a city that, just in the last decade, has attracted more than €30 billion in real-estate investment,[38] the project's legacy clarifies. Malterre-Barthes poses the central question: Is construction today unsustainable by design?[39]

Bosco Verticale suggests an affirmative answer. Despite pressure to address the built environment's material harm, efforts to mitigate construction and land use policy have not been proportionate.[40] Bosco Verticale exemplifies this evasion: it treats sustainability as checklist elements added to luxury development rather than fundamental reimagining of how we build and dwell in urban space. The buildings' aesthetic power is undeniable. Their capacity to capture imagination and generate global influence is proven.

Yet this influence largely serves to normalize climate adaptation approaches privileging technological intervention over material restraint, spectacle over substance, luxury consumption over collective benefit. As Ferrando suggests, future decades may remember Bosco Verticale as "architectural emblem of a brief and ultimately ephemeral zeitgeist," a moment when society believed technology could solve ecological crisis without addressing deeper questions of growth, consumption, and equity.[41]

As Milan grapples with corruption investigations, and as global architecture confronts its complicity in the climate crisis, Bosco Verticale's legacy serves as cautionary tale. Revealing the limits of neoliberal green architecture, Bosco highlights architecture’s incapacity to challenge growth paradigms from within. As architects & real estate developers transform ecology into commodity, the continued preference of technological spectacle over genuine material restraint suggests misaligned incentives.

Course correction, as Malterre-Barthes insists, is urgently needed. A correction that rejects greenwashing façades and focuses on redesigning to reduce material consumption, reject neocolonial resource exploitation, and challenge excessive real estate production.[42] Only through such fundamental questioning of existing economic models can architecture move beyond spectacles like Bosco Verticale toward genuinely sustainable futures.

FOOTNOTES

[1]: Bosco Verticale Overview (Milan: Stefano Boeri Architetti), 1.

[2]: Charlotte Malterre-Barthes, "On Architecture and Greenwashing," *The Political Economy of Space* 01 (2023): 1.

[3]: Davide Tommaso Ferrando, "Revisit: Bosco Verticale," *Architectural Review*, 67.

[4]: Ferrando, "Revisit: Bosco Verticale," 67.

[5]: Ferrando, "Revisit: Bosco Verticale," 67.

[6]: Ferrando, "Revisit: Bosco Verticale," 67.

[7]: Malterre-Barthes, "On Architecture and Greenwashing," 1.

[8]: Ferrando, "Revisit: Bosco Verticale," 69.

[9]: Bosco Verticale Overview, 1.

[10]: Malterre-Barthes, "On Architecture and Greenwashing," 1, citing David Harvey's concept of the "techno-fix."

[11]: Bosco Verticale Overview, 2.

[12]: Bosco Verticale Overview, 2.

[13]: Bosco Verticale Overview, 2.

[14]: Ferrando, "Revisit: Bosco Verticale," 72.

[15]: Ferrando, "Revisit: Bosco Verticale," 72.[16]: Bosco Verticale Overview, 1-2.

[17]: Bosco Verticale Overview, 2.

[18]: Ferrando, "Revisit: Bosco Verticale," 72.

[19]: Malterre-Barthes, "On Architecture and Greenwashing," 2.

[20]: Ferrando, "Revisit: Bosco Verticale," 69.

[21]: Malterre-Barthes, "On Architecture and Greenwashing," 1.

[22]: Ferrando, "Revisit: Bosco Verticale," 69.

[23]: Bosco Verticale Overview, 2.

[24]: Ferrando, "Revisit: Bosco Verticale," 72.

[25]: Nancy F. Castaldo, *Buildings That Breathe: Greening the World's Cities* (Minneapolis: Lerner Publishing Group, 2024),

chapter 4.

[26]: Bosco Verticale Overview, 1.

[27]: Bosco Verticale Overview, 1.

[28]: Ferrando, "Revisit: Bosco Verticale," 72.

[29]: Malterre-Barthes, "On Architecture and Greenwashing," 2.

[30]: Ferrando, "Revisit: Bosco Verticale," 72.

[31]: Ferrando, "Revisit: Bosco Verticale," 72.

[32]: Ferrando, "Revisit: Bosco Verticale," 72.

[33]: Ferrando, "Revisit: Bosco Verticale," 72.

[34]: Bosco Verticale Overview, 2.

[35]: Bosco Verticale Overview, 2.

[36]: Castaldo, *Buildings That Breathe*, chapter 4, quoting Simona Pizzi.

[37]: Ferrando, "Revisit: Bosco Verticale," 69.

[38]: Ferrando, "Revisit: Bosco Verticale," 74.

[39]: Malterre-Barthes, "On Architecture and Greenwashing," 1.

[40]: Malterre-Barthes, "On Architecture and Greenwashing," 1.

[41]: Ferrando, "Revisit: Bosco Verticale," 74.

[42]: Malterre-Barthes, "On Architecture and Greenwashing," 2.